Understanding Participation

What is children and young people’s participation?

The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) lays out a range of participation rights for children and young people, from freedom of expression to the right to information. A General Principle of the UNCRC is Article 12, which requires children’s views to be given due weight in all matters that affect them to inform relevant decision making at both an individual and collective level.

Participation is defined by the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child’s General Comment on Article 12 (2009, page 3) as describing: “ …ongoing processes, which include information-sharing and dialogue between children and adults based on mutual respect, and in which children can learn how their views and those of adults are taken into account and shape the outcome of such processes.”

All rights of children and young people are recognised to be interdependent and mutually reinforcing. This means no one right can take precedence over another and they must therefore be considered holistically. In practice this means that other children’s rights interact with Article 12 and support its fulfilment – such as the rights of non-discrimination and freedom to give and access information. Similarly, Article 12 and children’s participation rights also support children’s access to wider rights, including their rights to protection, provision of resources and prevention of exploitation and harm.

Children and young people’s participation in research

Over the last thirty years there has been an increasing recognition of the need to undertake research with children and young people. This follows the emergence of childhood studies and the growth in children’s rights discourse (Tisdall et al. 2023). Children and young people are now widely recognised as having expertise on their own lives and as social actors who can meaningfully contribute knowledge, experiences and views. Involving children and young people as active participants in research is therefore increasingly seen as a vital part of understanding children and young people’s lives and their related needs (Wright et al. 2024). This has led to a range of approaches to involve them meaningfully as research participants.

Some research has gone further, extending children and young people’s involvement in research to more engaged and collaborative roles – using what we might call ‘participatory research methodologies’. Participatory research is done with children and young people, rather than to them. It requires that children are supported to have meaningful opportunities for influence beyond simply providing data and children and young people are thus engaged throughout the research process. Broadly this means working with children and young people as co-creators or partners in research.

Subsequently, new participatory research methodologies have been developed to facilitate diverse children and young people’s involvement across various stages of the research process within social science, humanities, and health. Examples include multi-method approaches that utilise a range of methods, such as the ‘mosaic approach’ (Clark and Moss 2011), a technique that is often used when working with younger children or children with additional communication needs. Creative research practices can be closely aligned with participatory research and include photovoice, digital story-telling, walking tours and arts-based methodologies (see Brady and Graham 2018). All are underpinned by assumptions about a need for adult researchers to share power and influence with children and young people and to find ways to facilitate children and young people to express their views more fully across the research processes.

Digital tools and online participation with children and young people is also increasingly used and can facilitate interactions that may not be as possible through solely face to face engagement. This can include research with young participants that spans different geographies or for whom travel may be restricted (see Collins et al. 2020; Kustatscher 2020). In the context of the COVID-19 global pandemic, researchers increased their use of digital technologies to engage with children and young people in participatory research.

There is no shortage of methods that can be used with children and young people. However so-called participatory or creative methods are not always preferred nor accessible for all children and young people. Participation may have significant benefits for both the research and children and young people involved – but not necessarily (Tisdall 2015). Researchers should make explicit the key intended benefits and contribution of participation (McCarry 2012). Research with young survivors of domestic abuse suggests that the research needs to benefit them and be a positive experience, and, more importantly, it must impact on the lives of others experiencing abuse otherwise it is not worth their emotional and time investment (Houghton 2015, Houghton et al. 2023). These individual and collective benefits can then be included in evaluation frameworks to consider whether they were realised and provide a basis for gathering learning from the process and potential for improvement.

When deciding on which method to use we need to consider how different methods can address the research questions, facilitate children and young people’s involvement, and address ethical considerations.

|

Questions to consider:

|

Ways that children and young people can participate in researchChildren and young people’s roles in participatory research can look different in different projects and involve them in various ways. These might include some or all of the following:

- Providing expert advice to the research project

- Informing the research design processes, including setting aims, methods, and research questions

- Addressing ethics – helping to review research plans, pilot research tools or identify risks to, and protective strategies for, other children and young people

- Supporting or undertaking data collection – including as peer researchers or using creative research methodologies

- Supporting or undertaking data analysis – for example, prioritising emerging themes or through sense-checking findings

- Reporting on the research – for example, co-producing research outputs such as reports, posters, animations, or presentations

- Supporting knowledge exchange and impact through sharing research findings to influence change, possibly through dialogue with policy makers or funders

- Undertaking monitoring and evaluation – capturing learning about the research process and its impact

Within CAFADA, children and young people’s involvement has varied across different stages of the research and different sites. It included children and young people working: as expert advisors – helping to inform the research design; engaging in participatory arts projects to explore and express young people’s support needs; taking part in data analysis – prioritising and sense-checking findings from research interviews; engaging in knowledge exchangeevents to use research to influence change with policy makers; and helping to design and deliver aspects of the research dissemination.

Ways that children and young people can participate in research

Children and young people’s roles in participatory research can look different in different projects and involve them in various ways. These might include some or all of the following:

- Providing expert advice to the research project

- Informing the research design processes, including setting aims, methods, and research questions

- Addressing ethics – helping to review research plans, pilot research tools or identify risks to, and protective strategies for, other children and young people

- Supporting or undertaking data collection – including as peer researchers or using creative research methodologies

- Supporting or undertaking data analysis – for example, prioritising emerging themes or through sense-checking findings

- Reporting on the research – for example, co-producing research outputs such as reports, posters, animations, or presentations

- Supporting knowledge exchange and impact through sharing research findings to influence change, possibly through dialogue with policy makers or funders

- Undertaking monitoring and evaluation – capturing learning about the research process and its impact

Within CAFADA, children and young people’s involvement has varied across different stages of the research and different sites. It included children and young people working: as expert advisors – helping to inform the research design; engaging in participatory arts projects to explore and express young people’s support needs; taking part in data analysis – prioritising and sense-checking findings from research interviews; engaging in knowledge exchange events to use research to influence change with policy makers; and helping to design and deliver aspects of the research dissemination.

|

Questions to consider:

|

Resourcing children and young people’s participation in research

Children and young people’s participatory involvement in each of these research processes can require significant time, resources, and skill. Learning from our project has highlighted the importance of: time for careful collaborative planning and ongoing reflection; the value of working closely with specialist service providers as partners in our research processes; and the time needed for developing relationships of trust with the children and young people we work with. Ensuring that staff who undertake participatory research are properly supported is also key – and models of co-facilitation with two or more research staff have proved essential within participatory activities – particularly when addressing topics that may be sensitive.

Reciprocity or remuneration for children and young people’s contribution

Consideration should be given to appropriate reciprocity for children and young people who give time and expertise to engage in and support research. Reciprocity is different (and additional) to payment for expenses that children incur when participating in research. In many circumstances – particularly when young people are being asked to work alongside professionals being paid for a comparative role (e.g. on steering groups or as part of recruitment panels)consideration should be given to the level and form of reciprocity to offer parity with professional counterparts. Appropriate forms of payment will vary and are likely to be determined by a range of factors. These include (but are not limited to): the type of role and contribution children and young people provide; the lead institution’s systems and rules; practices of partner services through whom children and young people are recruited; and the age of participants. In some cases, it may be appropriate for children and young people’s participation to be on an unpaid or voluntary basis. In these cases, reciprocity may involve non-monetary offers provided individually or to groups of children and young people (e.g. a meal; an excursion; a donation to a service which children and young people access; certification). Partner projects and practitioners who know children and young people are likely to be able to provide advice on the most appropriate response, as can the children and young people involved. Additionally, there should be consideration of reciprocity (e.g. payment, donation, training) for the time and expertise of the practitioner/s involved, in supporting the child/young person pre, during and post involvement but also in partnership working e.g. designing sessions and methods to empower and include all participants.

|

Questions to consider:

|

Key principles for children and young people’s participation in domestic abuse research

Various models of children and young people’s participation have been developed to conceptualise and operationalise meaningful involvement in matters which affect their lives (see for example: Hart 1997; Lundy 2007; Shier 2010; Johnson 2014). Some of these have been specifically adapted for research (see for example Shaw et al. 2011; Lansdown and O’Kane 2014).

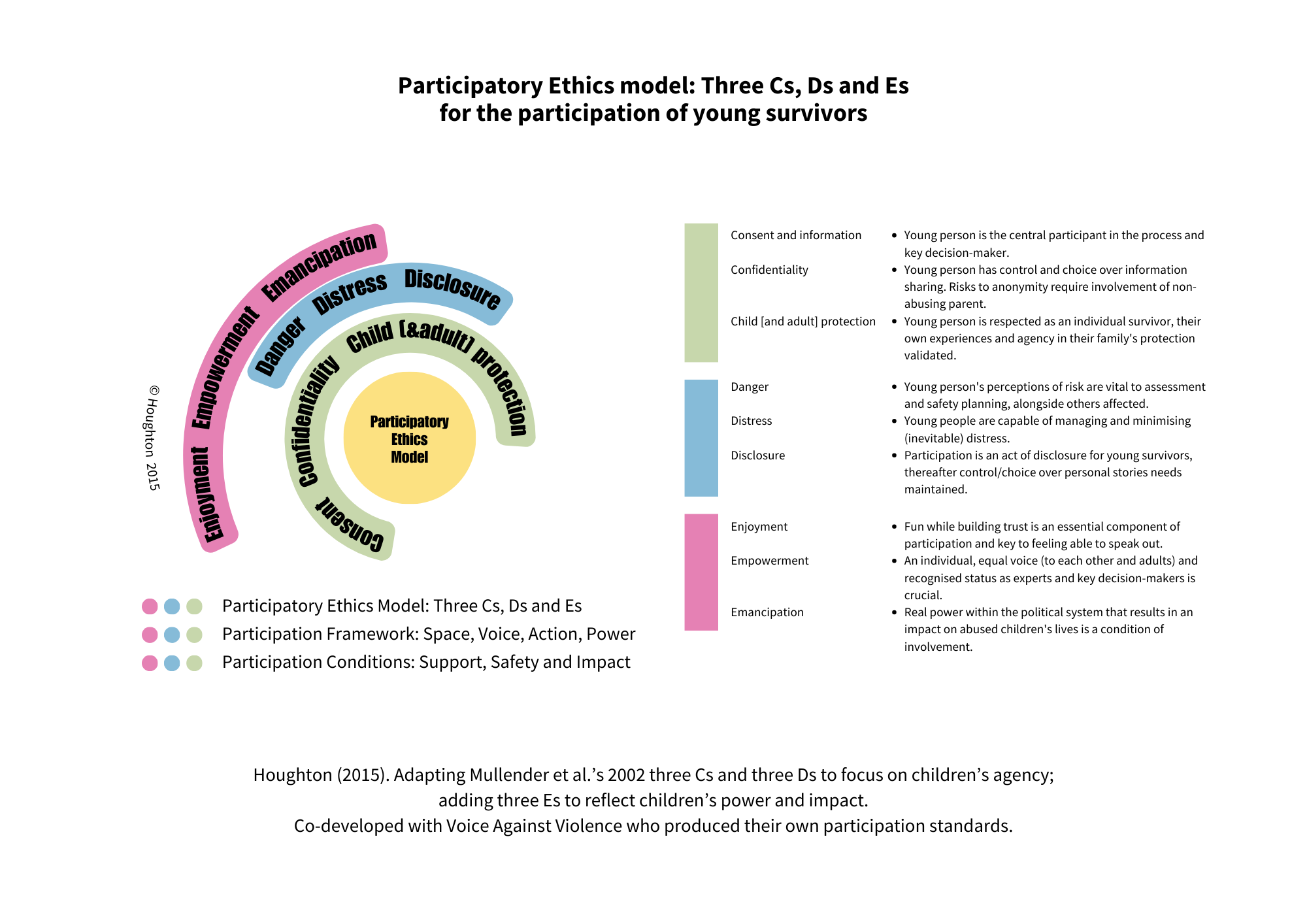

Working with young survivors of domestic abuse and gender-based violence across a series of projects, Houghton collaborates with young survivors of domestic abuse to develop a framework for children and young people’s participation (see Voice Against Violence, Houghton 2018, Everyday Heroes and Houghton et al. 2023). This draws on and expands Lundy’s (2007) influential model of children’s participation: space, voice, audience, influence). Houghton’s additions are rooted in experiences of domestic abuse and encourage even more active,inclusive and powerful roles for children and young people in research, practice and policy-making – to empower young survivors as agents of change:

Figure 1: Houghton’s framework for children and young people’s participation

Houghton’s framework has four components, which should all be present in participation activities involving children and young people who have experienced by domestic abuse.

- Space for survivors’/ children and young people’s action with support,

- Voice of the young experts that is heard, respected and supported to share ideas and solutions

- Action to ensure change where children and young people are part of decision-making, and

- Power to raise children and young people’s status and clout within the system and to hold decision-makers to account.

We have used this framework in CAFADA for both planning participation activities and our reflective learning and evaluation; we adapted it a little in our tools (e.g. using action/agency, power/influence).

|

Questions to consider:

|

Participatory research and young survivors of domestic abuse

Our participation toolkit was developed for CAFADA, which had a specific focus on domestic abuse. It was thus essential to situate the tools and our approach within the context of practice, research and policy addressing domestic abuse and the theoretical frameworks that inform how we understand and respond to the issue.

A feminist theoretical framework considers gender relations, power, and control as key factors of domestic abuse and other forms of gender-based violence (Kelly 1988; Stark 2009). Children and young people living with domestic abuse are direct victims of abuse (Houghton 2015; Callaghan et al. 2018) and are impacted negatively by coercively controlling behaviours such as emotional and financial abuse, isolation, and monitoring (Katz 2016). Child survivors of domestic abuse describe similar tactics of abuse to those experienced by adult survivors of coercive control, including the micro-regulation of everyday activities placing children and young people in isolated, disempowering and constrained worlds (Katz 2016).

Children and young people must be able to express their views without fear of the consequences. Children and young people growing up with domestic abuse may not have previously had opportunities to form and express their views safely or may have previously been let down or silenced by adults. Constraints on children and young people due to domestic abuse can contribute to disempowerment and lost confidence of survivors (Westmarland and Kelly 2013; Matheson et al. 2015). As a result, children and young people with experience of domestic abuse may have concerns about sharing their feelings and opinions.

Children and young people’s participation rights are inextricably connected to other human rights, including the right to be protected from abuse (UNCRC Article 19). Perceived tensions can sometimes exist between children and young people’s rights to participate in matters which affect their lives and efforts to protect children and young people from perceived harms that might arise from participating in research. Such tensions often emerge when navigating traditional institutional ethics procedures, which may tend towards risk-averse approaches. This can pose additional challenges to meaningfully engaging children and young people in research on topics considered sensitive, such as domestic abuse. However, assuming that children and young people with experience of domestic abuse will necessarily be harmed by participating in research risks excluding them and silencing their views, thereby exposing them to other forms of harm.

Recognising the relationships between children and young people’s interrelated rights to participation and protection can help to resolve these tensions – understanding that their participation in research – if managed thoughtfully and ethically – can be a positive experience that can contribute to their safety and wellbeing and that of others. Adopting an approach that is thoughtfully planned, agreed on beforehand and clearly structured can mitigate potential risks in children and young people’s participation in research and allow them to access a range of potential benefits associated with participation (Overlien and Holt 2018).

A more detailed consideration of the ethics of participation in domestic abuse research is considered in the next section of the toolkit.

Projects such as Voice Against Violence, Power Up Power Down, Everyday Heroes and Yello! have successfully partnered with young survivors of domestic abuse to influence policy-making in Scotland and beyond. Learning from young survivors’ perspectives on meaningful participation is vital to ensure that their views are not only heard, but also listened to and acted upon. This can challenge the dynamics of coercive control and improve practice and policy in line with children and young people’s views, experiences and solutions.

Summary of key points:

- Children and young people have rights to participation, as required by the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. Article 12 requires children and young people’s views to be given due weight in all matters that affect them.

- Children and young people can participate in research in a number of ways. Researchers must be transparent about which level and type of participation is possible and appropriate for the aims, objectives and theoretical frameworks of the research and within the context of available resources.

- A wide range of participatory methods have been developed, to engage children and young people in research activities. However, not all children and young people may find them accessible or preferable.

- Monitoring and evaluation of children and young people’s participation in research is vital to holding the project and team members accountable and ensuring ongoing learning both for the project and more widely.

- All team members and participants should be given clear information about the level of influence their contributions will have on the project.

- Participation in research can be framed by four elements: Space for action with support, Voice of the young experts, Action to ensure change and being part of decision-making, and Power to ensure children and young people’s status, clout and holding decision-makers to account.

- Ethical considerations of children and young people’s participation in research should recognise their contribution as social actors and co-producers of knowledge and the potentially positive benefits of research participation alongside risks.