Ethical frameworks

Our Ethical Framework

There is no one correct approach to applying ethical standards to children and young people’s participation in research, including in relation to research on domestic abuse. Following Alderson and Morrow (2020), we advocate posing ethical questions to prompt critical thinking about the process.

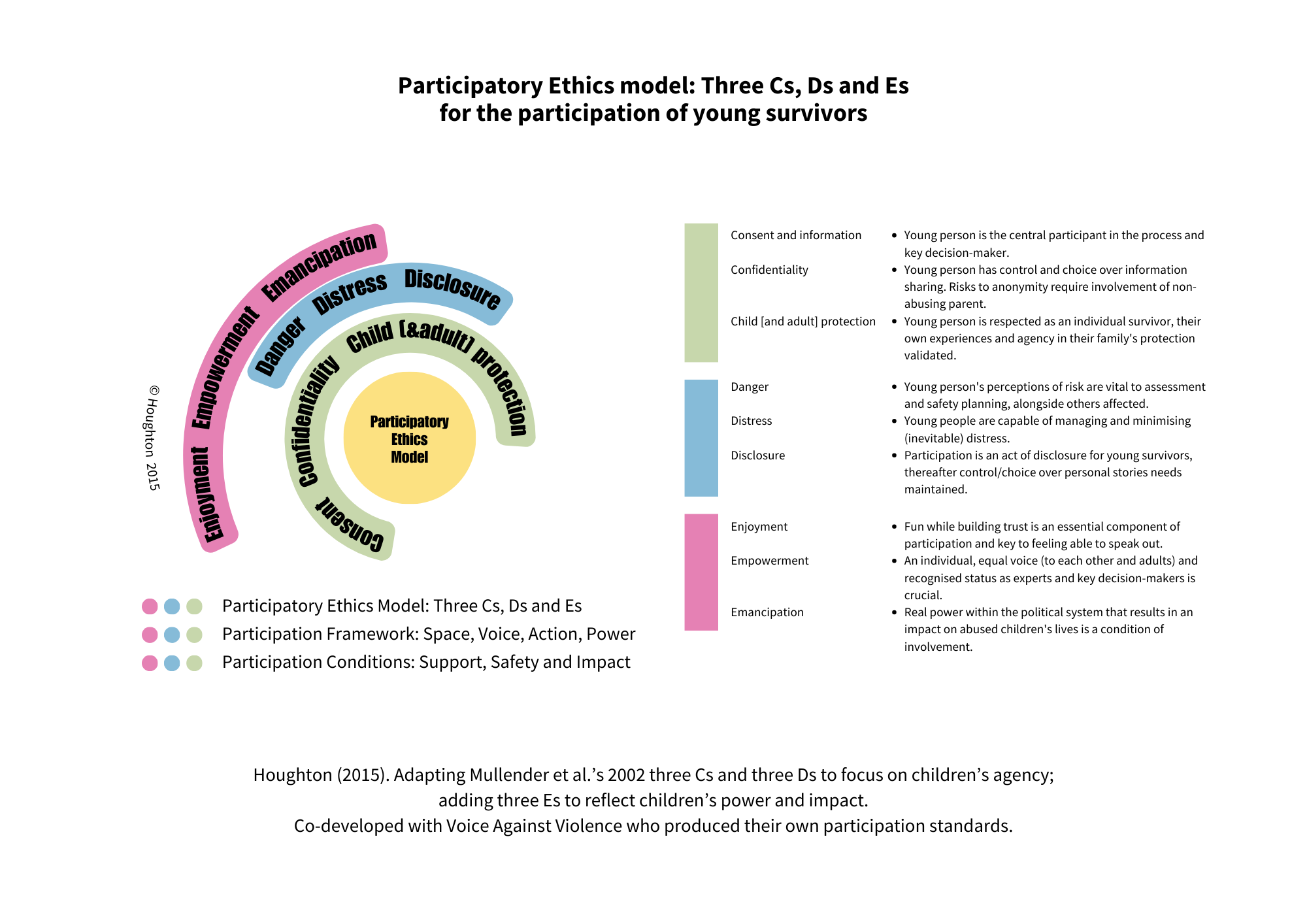

In this project Houghton’s (2015) model is used as our starting point (adapted from Mullender et al. 2002). It is a model developed in partnership with and for children and young people with experience of domestic abuse. It is accompanied by a Voice Against Violence Standards Booklet developed by young survivors to promote the participation of other children and young people experiencing domestic abuse and educate professionals.

Consent, confidentiality, child (and adult) protection

How do we gain informed consent from children and young people?

Negotiating informed consent with children and young people directly is essential from a human rights’ perspective. Informed consent requires children and young people to have an understanding of the research’s purpose and what involvement will mean and opportunities to ask questions. Accessible information and the support of a trusted worker/researcher is key to this. Consent should be recognised as an ongoing process, and children and young people must understand they can cease involvement during and after the research process. It may be legally required or beneficial to have the consent of legal guardians for children and young people to participate in research, particularly as safety planning is likely to need to include wider family and carers, in particular the non-abusing parent, but a children’s human rights approach would still necessitate that a child or young person’s participation in research is contingent on their active and informed consent, integrating their own assessment of risk.

Confidentiality and anonymity

As with all research, participants should be able to retain control over how their contributions are shared and with whom – particularly given the sensitivity and potential safety implications of identifying themselves with domestic abuse. Confidentiality and control over their own stories is particularly important to young survivors, this may extend to keeping their involvement in research confidential. Thoughtful discussions need to take place about talking of individual experiences in group settings and also how to balance children and young people’s needs for recognition of their contribution while protecting their right to anonymity and safety. In the context of domestic abuse, a child or young person being identified may in turn impact on the safety and anonymity of others. Where children and young people want to participate in activities that may compromise their anonymity, it is vital that decisions are made in discussions with a supportive non-abusing parent or carer. It should be made clear from the onset that where there are safeguarding or child protection concerns, confidentiality cannot be guaranteed – alongside information about what this may entail and the processes for sharing information.

Child, young person (and adult) protection

Children and young people must be recognised as individual victim/survivors of domestic abuse in their own right – and not just ‘witnesses’ to their parents’ abuse. The relational nature of children and young people’s safety must also be recognised – understanding that children and young people’s safety, wellbeing and protection is closely related to that of their non abusing parent, carer and other family members. Children and young people take on roles to protect themselves and others in contexts of abuse and this should be recognised. Careful safety planning which involves children and young people themselves, as well as their non-abusing parent or carer, is likely to be an important component of aspects of participatory research addressing domestic abuse.

Danger, Distress, Disclosure

How do we ensure the safety and wellbeing of participants?

Researchers must balance their research aims with the safety and wellbeing of participants. Safety and wellbeing are multi-dimensional, including physical, relational and emotional aspects. Considerations about the potential impact of a child or young person’s participation in research should take their own perceptions of risk and protective factors into account to inform assessment and safety planning. Both project workers and safe family members can provide a critical role in supporting risk assessment and safety planning with and for individual children and young people. This includes consideration of danger from the perpetrator (for the family, in certain locations, etc.) and also other considerations important to young survivors such as safety from stigma.

Anticipating and dealing with distress

Distress to children and young people should always be minimised but equally recognition should be given that research that focuses on domestic abuse may understandably surface difficult feelings. This does not mean that children and young people should not be involved in research, but rather that steps are put in place to respond – which take account of children and young people’s own skills in managing distress. If children and young people are accessing support services, it may be appropriate for a key worker or project worker who is known to the child or young person to be present (or nearby) to offer support before, during and after a participation activity. Most importantly, children should make their own ‘coping with distress and hard memories’ plans which might include time out, calling mum/a friend, time with a (second) researcher, support/counselling session, etc. and researchers should make plans to facilitate this.

Dealing with disclosure

When children and young people take part in research addressing domestic abuse, this often involves a degree of disclosure – identifying themselves as a victim or survivor of abuse. Children and young people must be supported to retain full control of what they choose to share of their experiences and with whom – with no pressure or expectation to do so. This includes preparation and co-developing ground rules for young survivors as individuals, as a group and for any adults they come into contact with (for example using third person questions, no direct questions, pre-prepared comfortable snippets of own experience relevant to subject discussed). To note that revisiting painful experiences in a supportive atmosphere can also lead to a positive reframing of the past.

Enjoyment, Empowerment, Emancipation

How do we make sure participation is fun and why does it matter?

Young people involved in previous participation projects have identified enjoyment and fun, and building trust as crucial to participation and speaking out: an equally important part of our ethical considerations to safety (see Houghton 2015). Integrating ‘teambuilding’ aspects (meals, activities, nice spaces/walks etc..) and ensuring research activities are creative and stimulating can contribute to positive working relationships, new friendships, build on trust, deepen engagement and also help to achieve project aims. Celebrating key moments/achievements is important and promotes recovery, as does inclusion of (non-abusing) family members at these times (for many).

Who is empowered and included within research?

For young survivors who often felt silenced by abuse and responses to it, speaking in their own voice and with equal voice to others is paramount. Ensuring each young person is heard (in their own way) and has a role in the project can build self-confidence, peer respect and validation, helping to feel release, relief and a sense of shared experience and moving on together.

Every methodological decision regarding research impacts on which children and young people are included and excluded from participating – and whether their views are respected and hold status. Researchers should consider how inclusive and accessible their research activities with children and young people are in relation to language, additional support needs, learning styles, and previous experiences. This includes considering how, where and when the research takes place and who might be included/excluded by those decisions. Researchers and those who are facilitating access to research participants should examine how exclusionary factors can be mitigated and involve children and young people in these discussions.

How do we consider and negotiate power dynamics?

Negotiating power dynamics is an important ethical consideration, when children, young people and adults are involved in research together. Young people tell us that it is particularly difficult to have their voice heard and respected when working with adults – this requires a shift in status for children and young people so that they are seen as young experts. Research and impact opportunities should be seen as a swapping of expertise, with children and young people’s voices and opinions of equal importance to the voice of adults, and that both are working together to achieve change. Access to those with power to change things (relevant to the research) is an important component of this, as is reciprocity in terms of payment, reward, and/or opportunities.

Adult researchers should be clear and honest with children and young people about their respective roles in the research, and the roles of others, including the level of influence children and young people can expect to have. Working with adult partners/decision-makers about trauma informed and empowering approaches in their engagement with children and young people who have experienced domestic abuse is a crucial part of preparation, covering all ethical considerations and focussing on methods to facilitate equal voice and expertise. Young people leading such engagement can facilitate this.

What does emancipation in research look like and why is it important?

Children and young people tell us that overwhelming they participate in research because they want to influence change in policy or practice. They also tell us that opportunities to see their contributions translation into real change should be a condition of their involvement. Projects therefore need to invest resources in ensuring influence and dialogue with decision-makers and ensuring feedback mechanisms to all those involved in the research. A key method of building trust and transparency is ensuring children and young people receive feedback about how they have influenced the research and subsequent efforts to influence policy and practice. Furthermore, partners and researchers should consider if and how children and young people can contribute to the change and action required and whether young survivors can monitor and evaluate progress and impact.

A related aspect of emancipatory research is to respect participation’s potential to be a powerful therapeutic tool. Of crucial importance to young survivors was the potential of participation to contribute to the therapeutic journey of recovery, help free them from negative effects of domestic abuse (including through positive experiences, shifting how they see themselves but also building CVs etc.) and build confidence in themselves and other children and young people to change the world they live in (see Houghton 2015, 2018).

Questions to consider:

- What training and preparation is needed for research team members and associated stakeholders, to ensure they are aware of and address the particular ethical considerations of involving children and young people with experience of domestic abuse?

- How will researchers respect the agency of children in risk and safety planning, alongside non-abusing parents or carers? How will this influence methods? How will participants be supported to make and implement their own plans, including for distress?

- How will each research activity provide specialist support as required before, during and after each participation activity, for children and young people with experience of domestic abuse?

- How can the involvement of children and young people in the research consider potential impacts on them, of domestic abuse, trauma and discrimination?

- Are there any specific ethical issues for your project? Are there elements that those involved – children and young people, researchers, stakeholders– are anxious or nervous about?

- How will researchers ensure children and young people’s involvement is enjoyable, emancipatory and empowering?

- How will children and young people contribute to early and ongoing ethical considerations? How will ethical considerations be monitored and discussed throughout the project?